|

Editors note: From 1964 till 1997 when I retired, I was a New York City Firefighter spending most of my career with Ladder Company 5 in the heart of Greenwich Village, Manhattan. Fire can be a comforting friend, but fire out of control is a deadly enemy. Fire knows nothing about time of day or night, nor does it care about ethnic background, religion or color of your skin. And, it strikes when you least expect it and many times on the hottest of days and the coldest of nights. Firefighters around the world are most affected battling blazes on extreme temperature days and nights. Thanks to a dedicated group of volunteers of The Salvation Army Canteen, such as the author of the story you are about to read, Jimmy Goetz, who made me and fellow firefighters warmer on some of the coldest winter nights with a hot cup of chocolate, so we could withstand the brutality of winter firefighting. Jim Moerschel

Serving the Fire Lines with the Salvation Army Canteen

by Jimmy Goetz

As a child of 6 or 7, I grew up on Bailey Avenue and 229 street in the northwest Bronx. Not far up the street was a firehouse, the quarters of Engine company 81 and Ladder company 46. That was my home away from home. Like most kids, my brother Brian and I were fascinated by fire trucks, loud sirens, blaring air horns and the firefighters hanging from the "back step" of "81" and the sides of ladder 46, which in those days was the traditional "hook and ladder," a tractor trailer complete with the firefighter perched high atop the rear, known as the tiller-man. We all dreamed of doing that job. My mother was the only lady in the neighborhood with a direct phone number to the firehouse. Brian and I were always there. Just about every single day. We became one of the guys and helped with firehouse chores, cleaned the guys cars, polished the fire trucks and began learning all about life as a firefighter. We even began talking like them. Firefighters rarely refer to their company as Engine 81 or ladder 46 to their comrades, but will proudly say, "I'm from 46 Truck." Or, another guy will say, " I'm from 5 Truck or 81 Engine." A "box" to us was not something made of wood or cardboard. But an alarm box and if a "box came in" it meant someone pulled it and the firefighters would respond. These responses are always called "runs" by any firefighter. Brian and I knew all the jargon. We were part of the team, just a little shorter. One firefighter in particular, John Maglione, used to take Brian and myself to his summer house up in Connecticut on some hot days in July or August. As we grew older, we really became part of the firehouse crew when sometimes they would let us jump on board and respond to fires when they knew it wasn't a big deal. In the years that followed, we expanded our adventures by hanging out with Rescue 3, 93 Engine, 45 Truck, 45 Engine and 58 Truck and the neat part was that on many occasions we rode on runs with all these companies.

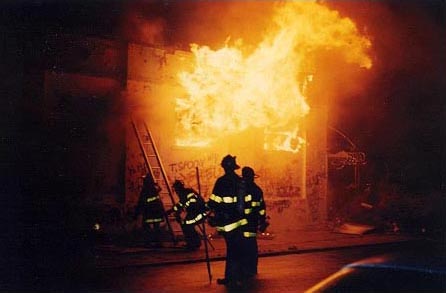

With this childhood introduction under our belts, Brian and I became dedicated fire buffs. One night we saw the Salvation Army Canteen truck at a big fire and there happened to be a friend working from my days with the Fire Explorers Post 543 that was located at the quarters of 43 Engine. We walked away with our hot chocolate and I said to Brian, "we go to all these fires anyway, why not join the Canteen and do a good service while we're here." He agreed and we went back to the canteen, filled out the applications. The rest is history. Over many years, we have driven the Salvation Army Canteen to every part of New York City, at all times of the day or night and especially in terrible weather conditions during icy, snowy, winter nights. We operated at the 1993 bombing of the WTC. The canteen was there for months and we used different crews of people at different times to serve the firefighters on the front fire lines. One time a child fell into a water tunnel in the Bronx and it took firefighters 21 hours to retrieve the boys body. Our boss came and wanted to relieve Brian and I at the scene after serving hot drinks and donuts for 11 hours, but we stayed for the duration, just like all the firefighters. Our childhood training and dedication learned at 81 Engine was so much a part of us and served us well. At the time that I worked at the Salvation Army Canteen, I was married and lived in North Yonkers. The distance to the firehouse in the Bronx from my house was about 10 miles and an average driving time depended on traffic and time of day, which was around 18 minutes. I once made it there in 12 minutes. Brian still lived in the Bronx, not far from 45 Engine and 58 truck on Tremont Avenue where the Canteen truck was stationed. I had begun to bring a camera along on all these fire calls and take pictures of fire ground action. When we would arrive at a fire scene, we would usually have to wait for an hour or more before we were allowed to open up the canteen truck, so this gave plenty of time to shoot photos of all the action. And, through the years I've amassed a big collection. Let me take you for a ride through the streets of New York on a very cold night, one of many we experienced over the years.

5th alarm in Brooklyn I went to bed around 11pm and I'm dead tired. Soundly asleep, I think I'm hearing an alarm clock going off. It can't be 7:30 yet! I pick up my head and it's 12:13am. Wait, it's the phone not the clock. My groggy voice answers the phone. "Hello, yes this is he." "3rd alarm in Brooklyn? Boeurum street off Flushing avenue? On my way!!!" Fully awake, I call Brian in the Bronx. Brian will beat me there and have the truck running and all set to go. I throw on plenty of clothes, heavy jacket, the whole nine yards. This is a real cold night. As I jump into my car, the first gulps of icy air wake me right up and I'm off for the Bronx. When I arrive, reliable Brian has the truck all set to go as planned and we waste no time responding. We have everything we need, but something is nagging me that maybe I left something behind, but I can't figure what. We head out of the firehouse using caution as we approach Boston Road. People have been known to run the red lights here, but we pass the intersection without incident, and we have our warning lights flashing and sirens wailing. As we head down the Sheridan expressway, the Chief in charge calls for a 4th alarm. Wow! Suddenly, I realize what I forgot. My camera!!! Yikes!!! Now I'm ticked and the pedal goes down a bit further. The toll lanes are packed at the Triboro Bridge and I thread the truck between the lines of traffic and get waved through by the toll taker.

We're monitoring the radio the whole way and now the deputy Chief calls for a 5th alarm and we wait anxiously for the "progress report." I press the pedal down a bit more. The chiefs aide begins the progress report: "4 Interconnected warehouses that house a mattress company. 6 stories 100 x 100 feet. Heavy fire in the basement of all four buildings with fire extending to the first and second floors rapidly. Fire is VERY DOUBTFUL. " Brian and I glance at each other. I'm thinking that this is like the mother of all fires and it is well below freezing. Brian must be thinking the same. Minutes later as we are on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, the chiefs aide gives another progress report. " All 4 buildings are fully involved in fire, special call 4 additional engines and 4 trucks - fire is still VERY DOUBTFUL." Now we're on the Kosciusko Bridge and we can now see the inferno. It looks as if all of Brooklyn is on fire. The flames are high in the sky and me with no camera. Engrossed in the radio report, I miss the exit we should take and race to the next exit at Kent avenue and wheel around towards Flushing. Just then a police car pulls up, the officer yells that he will escort us into the fire scene, which by now looks like the entrance to hell. The police car leads the way and escorts us right to this surreal looking scene. That's the first time we EVER got an escort.

Just as we turn the corner onto Boeurum Street one of the buildings collapses into the street, just missing some firefighters and a couple of Tower Ladders. The scene is like an action movie with flames everywhere, intense heat, buildings falling, but at the same time, ice forming on all the firefighters and their trucks from all the water being used to quell the fire. And me without my camera. I stop the truck in a good spot, get out and report in to the Deputy Chief at the command post. this lets him know that we are there and if he needs us we can begin serving some coffee, hot chocolate and donuts. The wind is really whipping and the wind chill has to be 5 degrees below zero. I return to the truck to see Brian standing outside. I'm thinking, what the hell is he doing out here instead of setting up to serve the hot stuff? The chief is about to send the entire first alarm assignment of firefighters to the truck for some warming up. Another problem. When I jumped out of the truck to report to the chief, I locked the keys inside. Now what were we going to do? We could get one of the side windows open, but neither Brian or I could squeeze through. Now here comes all these frozen firefighters, icicles dangling from their helmets, drained of energy, frozen to the core. And we can't get in the van. Luckily, one of the firefighters was skinny enough to slip through the window and we opened for business. Thank God!! Brian and I served the firefighters till we were relieved at 10am in the morning by the Canteen crew from Staten Island. I had plenty of time to reflect on all that happened. I left without my camera gear, missed the exit, got a police escort and locked the keys in the truck. But we served over 400 refreshments to all those frozen, dedicated firefighters. What a Night!!!

Strategy and technical information 1. Be out on the road with a scanner on to monitor fire traffic. If you are out there with your camera you are half way there. 2. When you arrive at the fire scene, take an overview look of the entire area and familiarize yourself with where the trucks and equipment will be placed. 3. Listen to the fireground channel! You will hear all the tactical reports from firefighters and chiefs letting you in on whats going on. You can get some great rescue shots by listening and paying attention.

4. Stay back out of the way of firefighters and other rescue personnel. The fireground area is a dangerous place and someone trying to get in too close can hinder rescue operations, cause someone to be hurt or get hurt themselves. USE COMMON SENSE. If you become a regular photographer at the fire scenes and you obey the rules there may become a time when you will be helped by the firefighters to actually get in close for some great shots. This happened to me. At the Van Buren street fire I was able to get those fantastic shots because I had earned the trust of the chief (B.C. Peterman) of the 18th Battalion. He wanted me to get some shots for him. 5. Personally, I like to get as close as possible without getting in the way. I have been burned a couple of times at fires, because I got too close, ie: Van Buren Street fire, the side of my face got burned from radiant heat. At a fire in Harlem one night, the building was sending off fire brands from the roof like Roman candles and some landed on me. Such are the hazards of being a fire photographer. 6. MOST IMPORTANT!!! Always keep your wits about you and keep listening to what is going on with the firefighting scene. Sometimes a routine fire situation can change suddenly and what appeared to be a stable building turns into a raging inferno, or a sudden collapse takes place trapping firefighters inside and killing some with falling debris outside. This is serious and risky business. My equipment is pretty standard. I use a Minolta X7A 35mm. The flash is a Vivitar 285HV zoom Thyristor model. This flash is good up to 100 feet at night, which is really needed to light up subjects. The battery for it is a Quantum 1A pack, which recycles very rapidly. I also use a Kalimar M-1 auto wind to move the film. My primary lens is a 35mm. I find that this size lens gives me ample coverage for almost any shot at a fire scene. If I need some real closeups, I switch for some shots using my 80mm-200mm. At night my fstop is wide open f2.8 and the shutter at 1/60. I shoot with Kodak 400 ISO color film. This film is very versatile for either day or night shooting. During the day, I shoot with an aperture of 5.6 with the auto speed setting. I really never protect my equipment and I have been very lucky over the years. I never use plastic covering or anything as I want the camera ready at a split second notice to capture the action as it happens, which is usually fast. I wish all who read this and become fireground photographers safe shooting. Jimmy Goetz

|