Rivers

to the Sea

By

Phil Maranda

“All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full.”

– Ecclesiastes

It’s been 10 years since I first ventured out my door

with the single purpose in mind of making photographs of every outdoor

subject imaginable. In that decade I’ve been truly blessed, having

made images in a multitude of locations around the world. My photographic

pursuit has taken me to Denali National Park in Alaska, The Canadian Rockies,

South East Asia, The Pacific Northwest, and the Caribbean, to name just

a few.

In nearly every location I’ve photographed, there has always been

water, from the smallest stream to the giant of them all, the Pacific

Ocean, and this element has been

enhancing my image making since the beginning. If there was

ever any doubt in a location as to whether or not there would be something

to make an image of, I’ve always looked for the closest water source—H2O

hasn’t let me down yet.

Botanical Beach is about 400 miles from my home and is one of my favorite

locations for making photographs in British Columbia. There is a wild,

untamed beauty

attached to the west coast of Vancouver Island, and few places

are better suited for witnessing this splendor first-hand than at Botanical

Beach. Massive storms and giant rollers from far out in the Pacific have

been pounding the windswept shoreline for millennia, helping to create

an enchanted symphony of ocean, land, and sky.

A scenic 83-mile drive from Victoria, the world-famous beach lies at the

end of the road on Highway 14 at Port Renfrew and marks the conclusion

(or beginning, depending where you start) of the Juan de Fuca Marine Trail

that stretches 30 miles along the coast to China Beach. Across an inlet,

the rugged and lengthy West Coast Trail begins, but it’s at Botanical

Beach where young and old can experience a vibrant ocean shoreline environment

without having to hike much more than a mile or two.

Photographers who visit Botanical Beach can spend their days roaming the

water’s edge making images of a plethora of tiny marine creatures

in the tide pools at low tide, hiking the forest trails, or watching the

waves while waiting for the rich pinks, oranges, and reds of a Pacific

Ocean sunset.

During the months of March and April, gray whales can be spotted offshore

while taking a break from their yearly migration from the coast of Mexico

to the waters of Alaska. Orcas also frequent the area along with Northern

and California sea lions.

The tide pools at Botanical Beach are filled with a seemingly endless

variety of life, some looking like they came from another planet with

names equally as odd. Purple sea urchins, giant green anemones, and gooseneck

barnacles can be found in large quantities, but it is the increasingly

rare, fiery red Blood Star that is a real treat to

view. The Blood Star is a member of the sea star family (once

called starfish), and its brilliant color makes it a perfect photo subject.

Other lucky photo-philes may encounter a dogfish shark or octopus stranded

in one of the pools.

Plenty of critters reside along the shoreline as well (cougars included),

and it’s not entirely unusual to share the beach with a wandering

black bear or two, even in the

winter since island

bears don’t hibernate. On any given day, photographers can find

themselves in the company of seagulls, bald eagles, harbor seals, and

river otters as well.

During the winter months, the west coast of Vancouver Island is bombarded

with numerous, fierce storms that begin far out in the Pacific, pushing

rain and high winds towards the coast. The intruding tempests wield massive

waves that crash on the beach. If you can handle the dampness, these giant

rollers are not to be missed. Not only are there no crowds this time of

year, but hearty photographers also get a front-row seat to witness the

extreme side of nature.

Across the Straight of Juan de Fuca from Victoria, on the coast of the

Olympic Peninsula, lies one of the most visually stunning (in my opinion)

coastlines in the United States. The beaches there are truly a scenic

photographer’s dream. Sea stacks, carved by wind and waves for thousands

of years, stand on the sandy beaches like

sentries guarding the shore, making great foregrounds for images

of the open ocean beyond. Pelicans, seagulls, and other sea-going fliers

glide on brisk offshore winds. And the sunsets rival that of any on Earth.

My favorite beaches include Ruby, First, Second, and Rialto, and they

can be reached approximately 150 miles from Seattle by following Interstate

5 to Olympia and then Hwy 8 and 12 sequentially until you pass the seacoast

town of Hoquiam where Hwy 101, The Pacific Coast Scenic Byway begins.

There are signs posted along 101 that announce each beach as you approach.

From Victoria, a ferry ride to Port Angeles puts you on Hwy 101. Follow

the signs towards the west coast of the peninsula.

There is no real best time of the year to make images on the beaches of

the Olympic Peninsula. Like at Botanical Beach, you’ll usually find

the biggest waves in the

winter months, but the weather can also be at its worst—wet,

cloudy, and chilly. Dressing in warm, waterproof clothing is a must if

you want to stay out on the beach long enough to make a few good images.

In the spring, summer, and fall, the weather is clearer, and at those

times of the year, it’s easy to spend all day at the beaches, roaming

along the water’s edge, checking out tide pools during low tide,

and scoping out just the right spot to make a beautiful sunset photograph.

One of my favorite locations for making sunset images is Phuket, Thailand.

Phuket is a resort island barely off the west coast of Thailand in the

Andaman Sea. The beaches are crowded most of the time during the days,

but close to sunset, the people head for the many outside restaurants

and bars for happy hour and great seafood. It’s at this time when

photographers can find themselves alone on the beach.

The shoreline in Phuket is a combination of sandy, palm-tree-laden beaches

and rocky outcroppings that when included in a scene can make for dynamic

foregrounds in sunset images. In the time I spent making images there,

the sunsets never let me down. Brilliant shades of yellows, oranges, reds,

blues, and purples painted the sky every night of the week in October

and allowed me to make a number of decent images.

At home, I’ve made most of my best river, stream, and waterfall

images in the mountains and valleys of British Columbia from the Rockies

to the Pacific coast. In the eastern part of the province, high in the

Canadian Rocky Mountain chain, glaciers melt in the summer sun and are

the starting point for several of B.C.’s larger rivers.

The mighty Fraser begins in the Rockies, and at its source, the river

is clearly nothing more than a small mountain stream. But as it flows

southwest on its 850-mile journey to the Pacific Ocean, dozens of tributaries

add to the volume of the river, and by the time it reaches the upper region

of the Fraser Canyon, the water has taken on the color of light clay and

the river has become intense.

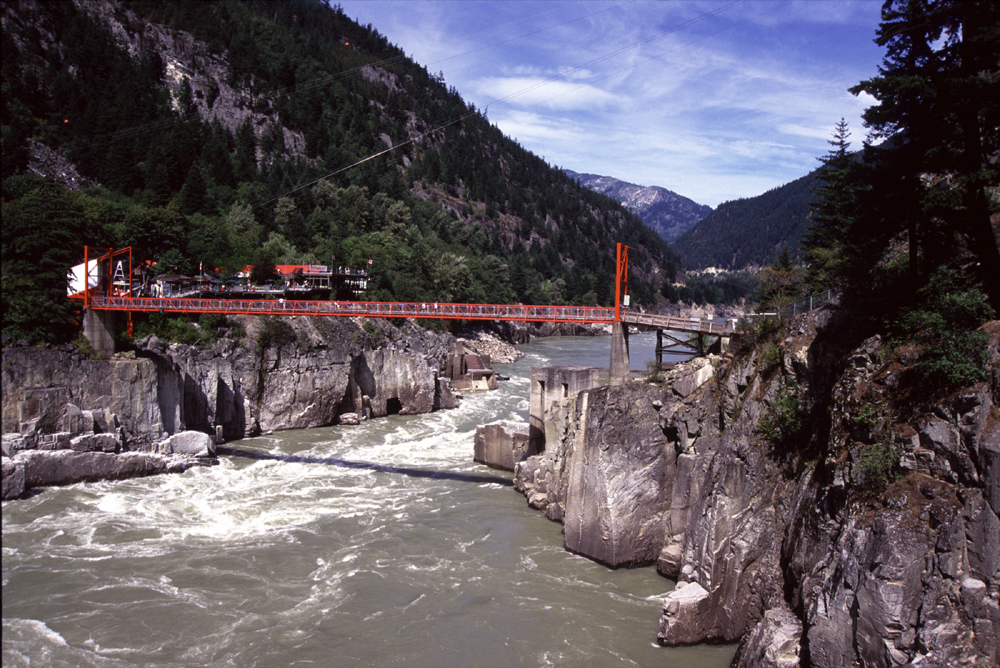

Within the 23-mile section of the Fraser River, which extends from Boston

Bar to Yale, the scenery becomes breathtaking, the rapids get wild, and

the water roars like thunder through the heart of a magnificent gorge.

Between the towns of Lytton and Yale, the river is at its absolute fiercest

and drops in elevation 278 feet at over five feet per mile.

The climax of the mighty Fraser happens at Hell’s Gate where the

water is forced through the narrowest point on the river, which is a mere

104 feet across. During the

spring runoff, twice the water can scream through Hell’s Gate in one minute than what descends Niagara Falls in the same amount of time. That’s 200 million gallons of water passing through the gorge every 60 seconds, which can reach speeds of up to 20 miles an hour. All this can be witnessed and photographed from various locations along the sides of the cliffs.

Gleaning great-looking images out of a water-based subject takes a little

preparation. Always make sure that you do a little research before heading

off to whichever location you plan to visit. Knowing the environment that

you are getting yourself into is paramount in having a safe, productive

trip.

Check into the expected weather conditions for the time during your visit,

and when journeying to an ocean shoreline, for God’s sake, always

check the tide tables—getting swept out to sea can ruin your whole

trip. This can be accomplished in a number of ways from using the local

marine forecast which is usually broadcasted on VHF radio to getting a

hold of the tables from a dive shop or outdoor adventure store in the

area you plan on visiting.

Pack your equipment in as watertight camera bags or cases as possible.

Pelican cases are a good choice, and Lowe also makes a fine waterproof

bag aptly named the DryZone, which can be completely submerged in water.

Once your gear is well protected from the environment, make sure that

you allow the same courtesy for yourself. Always take wet-weather clothing

on visits to oceans and rivers, lakes and streams, and wear a good pair

of hiking boots to provide some grip on slippery rocks.

Fill your camera bag with lenses from wide-angle to telephoto. Always

carry a sturdy tripod, especially when visiting the ocean—the high

winds there demand stability. Don’t be afraid of filters especially

when the use of one can add to or salvage a scene. I use polarizers often

to blue up skies, penetrate the surface of the water in tide pools, and

generally tone down any harsh light and reflections that can be found

near the water. In a lot of cases, warming filters, neutral density filters,

and skylights can also come in handy.

To get the most out of making photographs of water, I use Fujichrome Velvia

for the rich saturated emulsion this film provides. When using a digital

camera, find the most saturated color setting the camera offers—on

my camera there are several color modes to choose from, and I usually

pick the one that is specific for landscapes and nature. In choosing film,

use the sharpest, slowest, finest grain you can find but also bring along

a couple of rolls of faster film just in case the weather goes south and

the skies grey. With a digital camera, shoot with the lowest ISO rating

the camera has available in good weather and increase the speed as the

conditions demand.

Spend as much time as possible in the location you decide to photograph,

and always look around in every direction for subjects. In many cases

there are just as many photo ops behind you as there are in front. And

don’t be afraid to get your feet wet; sometimes the middle of a

stream may be the best place to plant your tripod. After all, we’re

outdoor photographers, and getting wet and dirty can be half the fun.

Of course there are thousands of streams, rivers, lakes, and many oceans

to make images at in nearly every part of the world. All you need to do

is get out and find the ones that someday you’ll call your favorite

places to make water images.

To view more of Phil Maranda’s work, visit his website at http://www.philmarandaphoto.com