NORTH SHORE FREERIDE

by Phil Maranda

The North Shore of Vancouver, B.C. is home to one of the wildest freeriding areas in Canada, perhaps the world. Not only is it stoked, it’s where the whole craze began over 11 years ago. There were only a few riders/trail builders constructing and challenging the radical trails that made up the freeriding areas of the Shore back then. They started with simple bridges to ride over logs and other forest debris, and then the whole thing went nuts.

Radical stunts started popping up everywhere, and with each new trail they became wilder and more challenging for the riders who possessed the metal to tackle them. The bridges got narrower and higher; soon skinnies, massive drops, and eventually wild-ass teeter-totters made up the more intense trails. These trails (which resemble army obstacle courses more than trails) were given names like Walk in the Clouds and the Flying Circus, each possessing their own unique obstacles or stunts. The excitement soon spread around B.C. and then around the globe, and to this day North Shore-style freeriding is one of the hottest forms of mountain biking around.

It had to be Digger’s (Todd Fiander) films that first grabbed my attention and really freaked me out. Watching mountain-bike riders catch huge air over the dried-up creek beds and drops on the North Shore trails and launch off buildings in and around Vancouver seemed totally radical. I just had to find out for myself what the Shore and freeriding was all about.

In mid-August I met up with Rich Vigurs, "Dangerous Dan" Cowan, and Thomas Vanderham who had offered to show me around the North Shore trails and assist me in making some images of their extreme mountain-biking antics. My first impression of the trio was that these guys seemed normal enough; there was no kamikaze look in their eyes or anything that would give them away. But like the old saying goes, "looks can be deceiving."

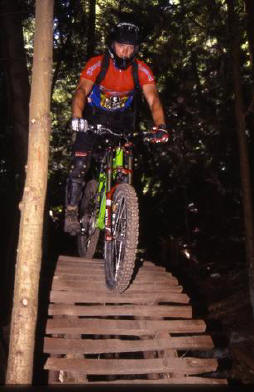

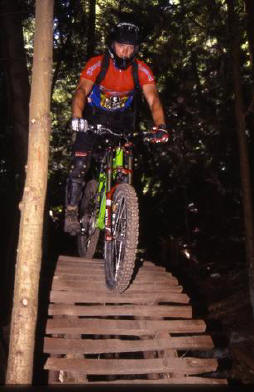

Watching Cowan and Vanderham attack a trail—appropriately named Walk in the Clouds for its plethora of ladder bridges—a mere 45 minutes later, quickly changed my mind. These guys are nuts for sure, I thought to myself as the riders dropped seven feet off the first stunt, The Abyss, then conquered (after several tries) a gnarly-looking teeter-totter-like stunt named the Skookumizer (it swivelled side to side and up and down) before cruising out of sight down the trail.

Around a bend in Walk in the Clouds, I finally caught up to the trio. (I was trying to negotiate, on foot, the slippery rocks, fallen logs, and other forest debris that littered the trail while Vigurs was riding around the really tough obstacles. They were all stopping to wait for me before tackling each new stunt.) I arrived just in time to watch Vanderham and Cowan each descend a narrow plank called the Needle Drop. One stunt soon flowed into the next, and before long we had traversed the full length of the trail and made it to the road.

The second trail that my guides took me on during the whirlwind tour was The Flying Circus. Cowan was responsible for this baby—he made it—and that was evident in the stunts that matched his preferred riding style of elevated skinnies and drops. "When I built The Flying Circus, people thought I was crazy; they thought I was psyched," Cowan said. "It’s a long story, but I had a tumor and was going through chemotherapy at the time. Everybody thought that building the trail was part of my therapy. They thought, Dan’s up there doing some crazy stuff. But nowadays there are quite a few people riding it."

We arrived at the Ridiculator a few minutes after starting our descent, and it was at that point that I realized just how lucky I was not to have been riding on the first day. Even though at the time the Ridiculator wasn’t finished yet, the rest of the trail would have wiped out an inexperienced rider like me, and seeing the skinny, ascending log ride reach a height of roughly 20 feet off the forest floor was enough to hammer the point home. The Ridiculator, my ass! I thought, staring up at Cowan and Vanderham standing on the top of the North Shore’s most radical stunt. Who’s going to be crazy enough to ride this? (If you did ride it, Dan, please send me a picture!)

Day two, Vigurs brought me a tough-looking mountain bike, and although I wouldn’t have to do much actual riding and could cruise around the stunts, the butterflies were building in my stomach just the same. Luckily for me, we didn’t have far to go from the parking area to where the Groovula began its rise into the forest. After five minutes of pedaling up a gradually ascending dirt road, we arrived at the narrow opening in- between two large trees that marked the beginning or end of the trail, depending on how you looked at it.

We were all forced to push the 40-pound bikes up the steep incline of the Groovula, and by the time we ran into Digger, I was puffing like a veteran smoker after ascending a flight of stairs. He’d been working on the trail since early in the morning, and when we stopped to check out his construction, I was thankful for the break. Digger’s trail-building skills are legendary on the North Shore, and after taking a close look at his handy work, it was easy to see why he’s the master. He’d piled up large stones on the forest floor then packed thick, dark soil into and on top of the rocks, building a berm that looked like it would last forever.

Our rest ended abruptly when Digger mentioned that he wanted Vanderham, Cowan, and a couple of other riders who would be arriving shortly to jump across a 26-foot creek bed as soon as he finished working on the trail. It would be just enough time for Vigurs, Vanderham, Cowan, and I to push our bikes the rest of the way up the Groovula and ride down. The idea was for me to make my way down the section of the trail from where we were to where Digger was laboring on the stunt and try not to kill myself in the process. Spending time at the top of the trail would also allow me to make a couple of images of Vanderham and Cowan launching off a giant boulder before they rode back to the creek bed.

After Vanderham and Cowan flew off the eight-foot-high hunk of rock several times, they took off down the trail and disappeared from sight. At the top of the Groovula, Vigurs gave me a full-face helmet, shin pads, gloves, and kneepads. "You can’t ride up here without the body armor," he mentioned. Then he showed me how to put on the protection that was supposed to save my butt in case of a wipe out. At the time it just didn’t seem to be enough equipment to protect me from a fall down the mountain.

It was time for me to try my luck at the easy route down the Groovula. I reluctantly mounted the bike for my ride. After I skidded down a short, steep, winding section of the path, Vigurs was confident that I could make it the rest of the way down without any assistance, and he cruised off leaving me alone to negotiate the slippery roots, small rocks, and tiny drops that made up the only way I was going to make it back to where everybody waited. Before long I was down at the creek bed feeling pretty relieved that that part of the ride was over, and I was still in one piece.

Vigurs, Digger, and I soon positioned ourselves in the dried-up, seasonal creek bed for the aerials that were about to take place, while Cowan, Vanderham, and the other riders who’d just arrived on the scene climbed a small hill that would provide the runway for the jump. Vanderham went first, rocketing down the trail at full speed, and then launched off the dirt ramp built up on the lip of the creek bed. He flew through the air effortlessly, releasing his hands from the bars, and then grabbed them again before landing on the other side. Through the lens of my camera, it looked like Vanderham was suspended on wires for a second before touching down.

One after another the riders launched over the creek while the rest of us shot stills and video of each mountain biker performing various tricks like table-tops, releases, and such. Then we moved on to a stunt where the riders jumped up onto a large, flat rock from another dirt ramp, flew off the boulder, landed on the other side, hit a man-made jump, and then cruised off down the trail.

By the time the riders were finished with the last stunt—I’d witnessed some pretty serious crashes and a lot of perfectly executed aerials that truly defied gravity in the time we spent at the creek bed—my two-day tour was coming to an end. I’d shot all the film I had and was hoping that I’d captured the essence of North Shore riding in all its diversity. We left shortly after that, and having ridden The Shore, just a little bit, I found myself at ease and wished the adventure had lasted longer.

Maybe with a little, well, a lot of practice, I thought, I could go back some day and ride with Vanderham and Cowan on an easy trail, and if I couldn’t keep up with them, maybe Rich would ride with me…. Above all else, I realized that North Shore riding is not just about the place or the stunts—it’s about pushing the limits of riding a mountain bike under the extremist of conditions with little concern for your equipment or your body. It’s about going big or going home!

End

The North Shore’s rainforest proved to be one of the more challenging environments in which I’ve ever made photographs. As it turned out, I had only two days for this assignment, and on both of these days the sky was clear and a blazing summer sun assaulted the canopy. This produced millions of hot spots (in the form of light penetrating to the forest floor) that were next to impossible to avoid.

The contrast of dark interlaced with extreme beams of light made it difficult to meter, and at the time I was certain that the images of the riders were going to be underexposed. Flash seemed to be the only thing that would salvage my shoot, and so I mounted an SB26 on my Nikon F100 with 28-70mm Nikor lens and started firing away.

Motion was another challenge as the riders were moving pretty fast. To freeze the action as much as possible, I panned the camera with the riders, used autofocus, cranked up the flash to its highest level, used as high a shutter speed as the Speedlight and camera would allow, and did a lot of praying. Fuji Provia 100 was the film of choice and that got pushed to ISO 200. That gave me a little extra shutter speed. In the end, some of the images—to my eye anyway—turned out pretty good considering the environment.