DRAGONFLIES

Stalking

the Aerial Gladiators of the Marsh

By Jim Moerschel

As a boy growing up in the

country, I recall spending countless hours on hot summer days

around a woodland pond where nimbled fingered 8 year old boys caught turtles,

frogs, toads,

spiders, grasshoppers and every conceivable creature within reach. But

I never remember

any of us ever catching those shimmering, darting dragonflies that patrolled

the shoreline

of our pond.

While photographing near a swamp in the summer of 1987,

I rekindled my boyhood fascination

of these flashing, shimmering predators. Of course, the

first step in photographing

any wild creature is to first learn as much as one can about their habits.

There are nearly 5000 species of dragonflies in the world and more than

300 in the United

States. Included in this family are narrow-winged and broad-winged damselflies,

common

skimmers, darners and club-tails. As I practiced stalking these creatures

I figured out why as

a kid I never caught any of them. They have the greatest sight in the

insect world. Large,

bulging compound eyes containing thousands of receptors called ommatidia

give them their

extraordinary vision. In addition, they can swivel the head freely in

almost any direction and

naturalists believe they can perceive motion at up to 40 feet away. So,

getting close to one is

not very easy.

Photographing dragonflies can be done at anytime of

the day with good results. Let’s start

with daybreak. With the sun low on the horizon I begin my walk through

a field, meadow

or swamp with the sun to my back. This allows me to not have glare in

my vision path and

the sunlight will illuminate the subject. The morning is also cool and

dragonflies are waiting

for the rising sun to warm the thorax muscles to allow flight. So they

can be found clinging

amongst the reeds and tall grass chilled enough to allow the photographer

a close approach.

Many of my best closeups have been done in the cooler time of day and

I’ve been able to

poke a 55mm macro lens and flash up to just a few inches away from these

skitterish little

critters. Over the years I’ve used several different camera/lens/flash

setups to capture dragonflies in a variety of habitats. Each has its good

points and bad points.

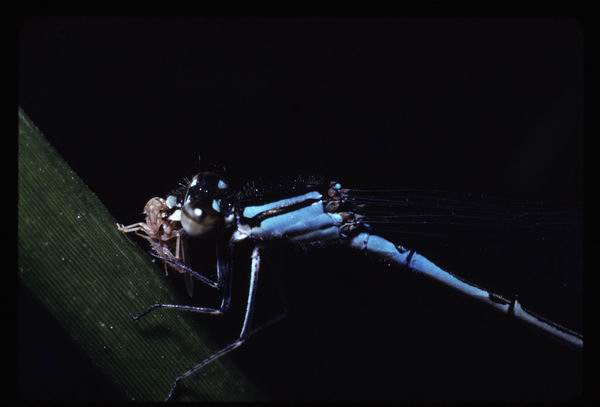

The first setup is to use a true macro lens that will

yield high magnification. My first lens

was a 55mm macro and I also used extension tubes to increase the magnification

depending on

my desired image. A single flash unit was attached to a flash bracket

that would place the flash

just over the lens and pointing to the tiny subject. With the single flash

being the primary

source of light and with an f-stop set at f16 good depth of field was

achieved. The main objection

with this system is that black backgrounds happen if there is no foliage

within a few inches of

the dragonfly.

This creates the feeling of a night scene, which

of course it is not.

By adding a second flash unit onto a specially built bracket the photographer

can aim

the second flash toward the foliage just beyond the dragonfly and with

this lighting

setup create images with a better illuminated background. This yields

a photo that depicts a

more realistic situation. This was the type of setup that was employed

for several years before

the modern generation cameras came along with matrix metering and auto

focus.

Today, the newer generation

cameras allow for more diversified shooting modes to

accomplish the goal of capturing these flashing gladiators of the swamp.

My Nikon N90s

and SB25 flash unit work nicely along with a variety of macro lenses to

do the job. A 180mm

or 200mm lens is a nice focal length to allow for nice magnification of

the subject and also

allows the photographer to stay back a little so as not to scare the dragonfly

off its perch.

I’ve also used a more unconventional setup using my close focus

400mm lens with one

extension tube to allow me to focus even closer than the lens would normally

allow. I mount

the flash onto the N90s hot shoe, place a diffuser onto the flash unit

to soften and spread the

light and place the rig onto my regular Bogen tripod. This sounds at first

like it would be

almost impossible to use, but in the right habitat it works very well.

I have a nice pond deep in the woods near my home that

serves as a great spot to find

and create dragonfly photos. Male dragonflies occupy a certain territory

around the perimeter

of the pond and each finds a branch or twig that is high up within its

domain to see potential

prey, rest or look out for predators or even rival males. These “favorite

perches” are what

I look out for. A male will fly off for a short period, catch a meal,

chase a rival and will return

back to the exact perch once again.

The strategy that I employ is to move my tripod very

slowly to about 7 feet away and stop.

I allow the dragonfly to get used to me being here and relax a bit. If

it flies off to feed, I will take

a nice “giant” step forward and freeze. By now the male has

returned to the perch. The next

time he leaves I move much closer and freeze like a “tree.”

When he returns I am motionless

and remain like that for awhile allowing him to accept me into the scene

as a “no threat” tree.

I begin to frame the subject, check my background, decide if I want to

shoot it vertical

or horizontal and decide whether my image size is desirable. If it is

not and I have to move

closer, I wait until the dragonfly leaves again and make any adjustments.

When he returns

I begin to shoot images. The electronic flash supplements the natural

sunlight nicely. I shoot

in aperture priority mode, set the lens at f11 and the rest is up to the

camera. I get to compose

and create.

I move about the entire perimeter of the pond in this

manner. The tripod is pushed along

in range of the next dragonfly and the same stalking technique is used.

There are always frogs

about and they become targets as well. Sometimes a small water snake will

be spotted and the long lens with close focus ability brings in a nice

image. By completing one revolution around

the pond will give me several nice images from different vantage points.

Since the dragonflies domain is both watery and muddy,

waterproof boots or fishing waders

can be handy to wear. I prefer old worn out sneakers, no socks and I wear

shorts. This allows

me decent footing and I don’t care about getting my feet wet. It’s

a hot summer day anyway,

so I slog around the shallows with my tripod or handheld unit to capture

photos that I would

not be able to get from the bank. Plus it’s a lot more fun.

Besides their acute vision, dragonflies will react strongly

to vibrations, such as the photographer accidentally brushing the bush

where it is perched. They will also react to

changes in light, so it is also important to avoid casting a shadow onto

the dragonfly if the

sun is over the shoulder. The idea is to move slow and be part of the

environment and they

will allow an approach.

During the early part of the summer the dragonflies

are in good shape and make nice

looking subjects, but toward the end of the season they have many scars

to show for the

gladiator wars they engage in. Males have to fight off rival males of

their species all vying

to occupy a favored territory and they sustain injuries to wings and legs.

While dragonfliesfly at one level over the pond catching and eating many

small insects, they are being watched

from a higher level by birds. Swallows swoop down in graceful arching

dives and snap them

up if a dragonfly is careless.

Many times the speedy and agile dragonflies escape

death, but

suffer a clipped wing. I have seen many of the shimmering gladiators with

one wing snipped

completely off. The injured dragonfly still can catch prey in this condition,

but it is never

quite as quick as it was before and eventually the relentless birds will

be victorious. I’ve

included a photo of a widow dragonfly with one wing clipped and this makes

a nice documentary

of the perils that they endure.

During mid to late summer one can witness the females

laying their fertilized eggs on

just about any pond. After being fertilized by a male, the female will

fly out over the pond

and drop near the surface of the water and flick her abdomen in a “slapping”

motion allowing

the eggs to drop out into the depths of the pond. The male will accompany

her and guard her

and even some times supports the female just above the surface. It is

at this time the female

is most vulnerable to being snatched by an alert fish lurking just below

hidden in the reeds or

lily pads.

For some really interesting photos, try facing the low

sun and find a dragonfly with

the resulting back-lighting illuminating the wings. The on-camera flash

unit will become

the main front-light to light up the near side of the dragonfly and a

nice image will be added

to your collection. Sometimes silhouettes can be very affective. With

the same back-lighting

situation turn off the on-camera flash unit and make sure the dragonfly

is positioned against

a lighter background that is in the direct sunlight. A profile shot is

better to show the body

of the subject and by spot metering the lighter background to obtain the

exposure a nice dark

subject will be silhouetted against the background.

Photographing these fascinating insects has always been

a pleasurable experience,

both satisfying a primeval urge to hunt and providing me with a nostalgic

sense of adventure

as I explored the miniature world with my macro lenses. Of greater importance,

it satisfied

my need to communicate a message about nature – of its beauty, its

creatures, its serenity,

its fragility, and yes, of its harshness. For a moment at least, it is

again, a hot summer day

around a woodland pond and my hands are again those of a nimbled fingered

8 year old boy

still trying to catch that elusive dragonfly.